Engaging parents and families in their child’s educational journey is key given its association with students’ academic success and classroom behavior (Fan & Chen, 2001; McCormick et al., 2013). One component of family engagement is school-home communication (Epstein, 1995). School-home communication describes bidirectionally sharing information from both spheres of the child’s life. Schools are encouraged to establish regular communication that is delivered through multiple modalities (Conus & Fahrni, 2019).

While the short-term goal of teacher-provided communication is often to provide information about a child’s progress and needs, this task should be completed within the overall aim of developing a sense of partnership between school staff and parents. In general, parents may expect that teachers will be the ones to initiate communication (Conus & Fahrni, 2019). Within communications, teachers should emphasize their respect for parents’ perspective and approach towards their child’s education (Lockhart & Mun, 2020). A sense of trust and connection may only develop when teachers attempt to engage families as active participants in their child’s education (Lockhart & Mun, 2020).

In establishing any communication, it is important to think of the backgrounds of all parties involved. Culturally and linguistically diverse parents may have different values from those expressed in the classroom (Gonzales & Gabel, 2017). For example, many teachers in the United States expect parents to act as advocates for their children, while in some cultures parents are expected to go along with the teacher as an authority on educational matters. Sometimes, this scenario results in school staff exhibiting a negative attitude, which subsequently leads to decreases in trust. Further, language differences can affect parents’ ability to both receive and provide information about their child (Gonzales & Gabel, 2017). Reaching each student’s family may not follow a one-size fits all approach.

Considering how best to engage families may seem daunting, especially when school-home communication has not yet been well established with a family. School-home communication may be further strained when strategies typically used during in-person learning do not easily translate to a virtual context. The following strategies may help classroom teachers develop school-home partnerships and increase parent engagement.

School-Home Communication Tips

- Self-Reflect (Lockhart & Mun, 2020). Engage in self-reflection regarding your perceptions of students’ families. You can further explore your own biases with assessments such as those available here. Then, carefully consider how various identities and demographics (i.e., cultural, socio-economic status, citizenship, etc.) may influence the actions of each student’s family. Continual reflection supports trusting and respectful attitudes, which translate in interactions with both parents and students.

- Personalize invitations to school events (Shajith & Erchul, 2014). When you are planning to attend a school event in-person or virtually (parent-teacher conferences, math night, a bake sale, etc.) send home notes to personally invite your students’ families. If you have students in your class whose parents do not speak or read English, reach out to the ELL Teacher in your building to help you translate (or to check your work if you used Google Translate).

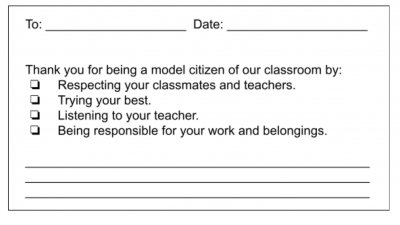

- Send home praise notes regularly (Howell et al., 2014). Many times, parents associate home-school communication with something negative about their child. Praise notes are positive, quick, and low-cost, and they have the added benefit of communicating classroom expectations to students and families. You can also use this method to provide specific praise to students who might be uncomfortable receiving praise in front of the whole class. Specific praise notes home can be short written statements which acknowledge desired student behaviors. They have often been used to increase appropriate behaviors and to strengthen teacher-student relationships. During virtual learning, praise notes may also help communicate virtual learning expectations to parents (especially when they are present to witness the child’s behavior), which may then help them better support their child at home.

This technique is often used as part of whole-school efforts to implement PBIS (Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports). To develop praise notes in your classroom, create a paper or web-based form that includes a space for a student name, a shortened list of expectations you are looking for that you can check off, and a space to include a sentence or two on what the student did specifically that you would like to reinforce. You can find a few templates for what these might look like here as well as our template below. Next, introduce the concept to your class and let them know that when you see them meeting or exceeding classroom expectations (whichever makes more sense for your class), you will give them a note to bring home (or send an email to their parents/send them a note on Google Classroom depending on your current classroom environment and what works best for you). You may also choose to let families know about this new strategy so they know what to expect. Create praise notes throughout the day, as you deliver specific praise verbally to your students about classroom behavior.

Further Reading and Resources on Engaging Families in Your Classroom:

- https://archive.globalfrp.org/family-involvement/publications-resources?topic=1

- https://www.edutopia.org/home-school-connections-resources

- https://www.tolerance.org/professional-development/family-engagement

- https://www.understood.org/en/school-learning/for-educators/partnering-with-families/eight-tips-to-build-a-positive-relationship-with-your-students-families?_ul=1*1g372f6*domain_userid*YW1wLTBVd014VEh5TDdhOF96MGR2S3hadUE.

- https://journals-sagepub-com.ezproxy.lib.uconn.edu/doi/pdf/10.1177/0013175X1209000306

- https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1149130.pdf

- https://globalfrp.org/Articles/Family-Engagement-Game-Brings-Theory-Into-Practice

References

Caldarella, P., Christensen, L., Young, K., & Densley, C. (2011). Decreasing tardiness in elementary school students using teacher-written praise notes. Intervention in School and Clinic, 47(2), 104-112. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053451211414186

Conus, X., & Fahrni, L. (2019). Routine Communication between Teachers and Parents from Minority Groups: An Endless Misunderstanding? Educational Review, 71(2), 234–256.

Epstein, J.L. (1995). School/Family/Community partnerships: Caring for the children we share. The Phi Delta Kappan, 76(9), 701-712.

Gonzales, S. M., & Gabel, S. L. (2017). Exploring Involvement Expectations for Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Parents: What We Need to Know in Teacher Education. International Journal of Multicultural Education, 19(2), 61–81.

Howell, A., Caldarella, P., Korth, B., & Young, R. K. (2014). Exploring the Social Validity of Teacher Praise Notes in Elementary School. The Journal of Classroom Interaction, 49(2), 22–32.

Lockhart, K., & Mun, R. U. (2020). Developing a Strong Home–School Connection to Better Identify and Serve Culturally, Linguistically, and Economically Diverse Gifted and Talented Students. Gifted Child Today, 43(4), 231–238. https://doi.org/10.1177/1076217520940743

McCormick, M. P., Cappella, E., O’Connor, E. E., & McClowry, S. G. (2013). Parent Involvement, Emotional Support, and Behavior Problems. Elementary School Journal, 114(2), 277–300. https://doi-org.ezproxy.lib.uconn.edu/10.1086/673200

Shajith, B. I., & Erchul, W. P. (2014) Bringing parents to school: The effect of invitations from school, teacher, and child on parental involvement in middle schools. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology, (2)1, 11-23, DOI: 10.1080/21683603.2013.854186